Art

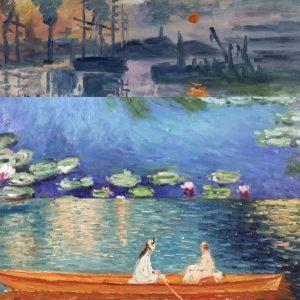

THOMAS KINKADE AND CLAUDE MONET: IMPRESSIONS IN THE LIGHT

From landscapes to lighthouses, from cottages to cabins, from mountains to Main Street, Thomas Kinkade captured the essence of nature and glimpses of Americana.

However, Kinkade is best known for his ethereal works of lush landscapes and colorful cottages with a fairytale feeling. His stone cottages nestled within a forest surrounded by secret gardens and sparkling streams invite the viewer in.

However, Kinkade is best known for his ethereal works of lush landscapes and colorful cottages with a fairytale feeling. His stone cottages nestled within a forest surrounded by secret gardens and sparkling streams invite the viewer in.

His paintings vibrate with a stillness and quiet magic, providing a respite, a place to hide away from world weariness and worries of everyday life. Delicate and dreamy, Kinkade’s works are eye candy for the spirit, with a lightness that lifts the spirit.

All artists derive their inspiration from somewhere, something or someone, whether conscious or unconscious. For Kinkade, he consciously mined his inspiration from his faith, from nature, from the world around him.

There are striking similarities between Thomas Kinkade and the great Impressionist master Claude Monet. Perhaps unconsciously Kinkade’s greatest stylistic influence was distilled from Monet’s masterpieces. Both painters provide a paradise, a peaceful retreat for the observer, and a serene majesty that soothes any irritation.

There are striking similarities between Thomas Kinkade and the great Impressionist master Claude Monet. Perhaps unconsciously Kinkade’s greatest stylistic influence was distilled from Monet’s masterpieces. Both painters provide a paradise, a peaceful retreat for the observer, and a serene majesty that soothes any irritation.

With gardens bursting in colorful blooms, to the shimmering ripple of reflection on the water’s surface, how could one not draw the conclusion that Kinkade was influenced by Monet? Some might think it heresy to invoke the two names together, but like it or not, Kinkade’s modern works are an expression of Monet’s lightness.

Rather than anesthetizing the senses, the saturated pastels, multi-colored hues and an evanescence to both Monet’s and Kinkade’s works provide a soft glow of soul.

Parallels between Monet’s Artist Garden at Giverny and Kinkade’s many garden paintings such as Garden of Grace, while not exact, can be drawn. Both display purple and pink hues bathed in soft light.

Other examples of similarities?

Monet’s Japanese Bridge and Kinkade’s bucolic Blossom Bridge. While the latter does not have the fine composition of Monet, both exude warmth, of immersing oneself in the waters under the bridge.

Monet’s Garden Path at Giverny and Kinkade’s Savannah Romance both take the viewer by the hand to lead them down a pathway, through nature, towards a final focal point with a sense of direction, but completely unhurried.

There are other examples exhibited if one opens up the mind and lets down any sort of inherent prejudice against Kinkade as kitsch. Instead, if one views Kinkade as paying homage to Monet the master, a tiny crack in the psyche widens to allow the possibility of a kinship in light