Art

Salvador Dali’s Adventures on the Silver Screen

Salvador Dali is a preeminent figure on the wall of most well-known art museums in the world. His personality and his great ideas pulled up from his never-ending dreams made him stand out from the crowd. He always came with themes that were never used before, and if they were, the atmosphere created with the brush was definitely unique.

Dali couldn’t stay connected to only one art domain. He wanted to try them all: beginning with painting, continuing with writing in newspapers, making impossible photographs and ending in creating movies side by side with the great directors of the times. The surrealist manner he developed in his paintings, spread to the movies he created. By doing so he had not only begun a new era in the field of painting, but also in cinematography.

Dali couldn’t stay connected to only one art domain. He wanted to try them all: beginning with painting, continuing with writing in newspapers, making impossible photographs and ending in creating movies side by side with the great directors of the times. The surrealist manner he developed in his paintings, spread to the movies he created. By doing so he had not only begun a new era in the field of painting, but also in cinematography.

He first flirted with movies when the cinema industry began in 1929. For his first cinema experience, he participated in making the Un Chien Andalou (“An Andalusian Dog”) movie, with Luis Bunuel. The silent movie had a surrealist inspiration, and it presented the principles of psychic and irrational automatism. The scenes are the result of two authors who’s imagination does not leave room for any interpretation and rational logic.

The unique narrative flow that doesn’t use the initial “once upon a time” can be described in terms of then-popular “Freudian free association.” Bunuel was the one that came with the idea of making such a movie. He told Dali at a restaurant one day about a dream in which a cloud sliced the moon in half “like a razor blade slicing through an eye.” Dali was already fascinated with the world of dreams, by including them in his paintings, so he developed the idea by adding descriptions of his own dreams, such as a hand crawling with ants.

The collaboration between the two was a success from the start. They both were fascinated by what the psyche could create, and decided to write a script based on the concept of suppressed human emotions. Dali perceived this film as a figurative and intellectual revolution, as he wrote in his memoires: “The film has the success I had expected. In one evening, this film had destroyed a decade of pseudo-intellectual postwar avant-garde.” The “Honey is sweeter than blood” and “The Great Masturbator” paintings have details and symbolic elements that inspire some of the movie scenes.

The film was initially released to a limited showing in Paris, but became popular and ran for eight months. After making this movie, Dali leaves France and returns to Catalonia in order to find himself. He starts painting clear and surrealist images such as photographs. These creations become typical for his style. One of these works is called “Das Ratsel der Begierde,” now housed by the Monaco Pinakothek der Moderne.

The film was initially released to a limited showing in Paris, but became popular and ran for eight months. After making this movie, Dali leaves France and returns to Catalonia in order to find himself. He starts painting clear and surrealist images such as photographs. These creations become typical for his style. One of these works is called “Das Ratsel der Begierde,” now housed by the Monaco Pinakothek der Moderne.

The Surrealists become even more fascinated by the Catalonian painter’s talent after he begins working for the second time with Luis Bunuel for the film “L’Âge d’or” (“Golden Age”). If during their firt movie, Bunuel and Dali had a great connection, now they come with different ideas in how to make the movie. Fascinated by the solemnity of Catholicism, Dali wants to introduce “many archbishops and relics” in the film. Bunuel perceives these ideas as a movement against the clergy.

Therefor, because of the different interpretation of the script and the violent episodes during the first screenings of the film at Studio 28, the two artists stop collaborating. By the time the film went into production, Bunuel and Dali had a falling out, and so the painter had nothing to do with the actual making of “The Golden Age.”

However, the film scandalized the public and was withdrawn from the market. A group of young right-wing extremists destroyed the hall in which the movie was projected. Dali exhibits his own works in the cinema foyer, along with other surrealist artists. The only painting saved from the fury of the demonstrators was “Invisible Woman sleeping, horse and lion.” Dali offers an explanation for this film:

“Writing together with Bunuel for the topics in ‘The Golden Age,’ I wanted to present the ‘conduct’ of a man hunting for love through degrading and patriotic human ideals, and other miserable mechanisms of reality “.

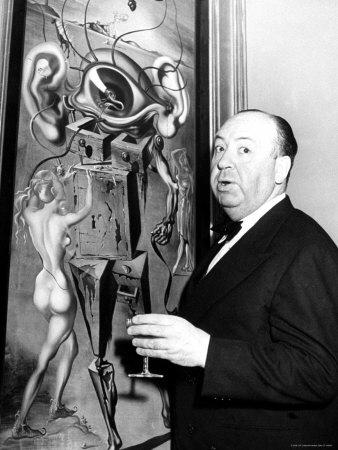

However, Dali doesn’t give up on his cinematic passion, and he continues to collaborate with great directors until the late 70s. In 1945, the artist creates the scenography for Alfred Hitchcock’s movie, “Spellbound,” which is based by Francis Beeding’s novel, “The House of Dr. Edwards.”