Art

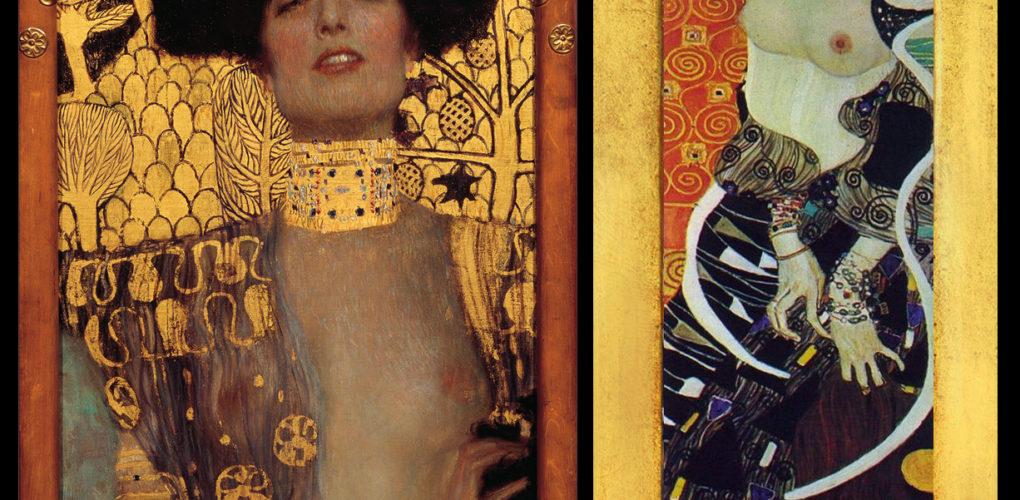

Gustav Klimt’s Judith and the Head of Holofernes

The dark night had fallen over Bethulia. A (symbolic) place in Jerusalem about to be taken and destroyed under the orders of Nebuchadnezzar, the king of Assyria. General Holofernes had been dispatched to take vengeance of all the western nations who would refuse to worship the king alone, occupying all the territory along the seacoast. Bethulia would be next. News had come to Judith, a virtuous widow who was as brave as beautiful. On that night, Judith left the city surrounded by the enemy’s army and finds her way into Holofernes camp, where a banquet was taking place. As she finds the man who desired her, she attracted him to his tent, seduced him, served him wine to the point of weakness, and decapitated him with his own sword. This is the biblical story of The Book of Judith, the woman who set her people free and inspired at least a hundred and forty-one works of art – from Donatello and Botticelli to Rembrandt, Goya, and Caravaggio.

Gustav Klimt – the Austrian symbolist son of a bohemian gold engraver – had his first take on Judith‘s theme in 1901. It was also the opening work of his “golden period” shown for the first time at the 8th International Art exhibition in Munich. In this rendition, there is no sword, no blood, no heroic manner. Instead, there is a powerful femme fatale looking down on the viewer, painted in oil and gold flakes, caressing a dead man’s head. The model, Adele Bloch-Bauer (wife of wealthy industrialist and allegedly Klimt’s lover) embodied this character with a hint of triumph and perversion.

What was expected to be a story about the courage of the commune against tyranny was crystallized by Klimt with an utmost erotic charge. The heroin expected to be a virtuous, God-fearing creature, reveals an undertone of a righteous cold murderer. On his approach, Klimt completely disregards the narrative – and almost discards the man by “cropping” his head at the right margin – to suggest an aroused woman barely covered by a beautiful gown, with eyes half-closed, lips apart, holding Holofernes’ head close to her waist.

Unlike most artists who portrayed a heroic and desexualized character – and unlike the Bible itself who portrays Judith as a pious woman – Klimt focuses on the sexual tension even after the decapitation was performed. Even comparing to Judith II, created by the same artist eight years later (1909), Judith I is incredibly daring. Whilst on the second canvas we can see a fierce and masculine woman, in a cubist style, carrying the general’s head in a basket; the first one conveys an unsettling image of a violent fantasy entangled with an eroticized death.

Judith and the Head of Holofernes touched the fine line between violence and lust, like a dominant lover who has met the extreme. To complete the eccentricity, Klimt asked his brother George to create its golden frame and engrave “Judith and Holofernes” on it, separating Judith from Salome – who beheaded Saint John the Baptist on another biblical tale. This irresistible darkness that he explored shamelessly, still makes justice to his all-time fame of one of the most controversial artists of the twentieth century.

“Judith und der Kopf des Holofernes” is today displayed in the Österreichische Galerie at the Belvedere Museum in Vienna, Austria to the great awe of thousands of tourists every year. For all other art lovers, Overstock Art provides hand-made oil reproductions, stroke by stroke, of Klimt’s greatest works for those who wish to take a little lust home.