Art

Henry Ossawa Tanner – Man of liberating talent

Henry Ossawa Tanner was the first of nine children, born on 21 June 1859 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He was named Ossawa in honour of John Brown, the abolitionist who commanded at the Battles of Black Jack and Osawatomie. His father, Benjamin Tucker Tanner, was a Bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal church – the first independent black denomination in the US – and a lifelong political activist. His mother, Sarah Miller, was one of many born into slavery that escaped to the North through the Underground Railroad.

In 1868 the family moved to Philadelphia, where he attended the Roberts Vaux Consolidated School for Colored Students until 1877. He was expected to become a minister like his father, but he knew he wanted to be a painter at 9, when he first saw a landscape artist at work whilst wandering about Fairmont Park. The idea had little encouragement from his father who apprenticed him in the flour business after finishing school. Little he knew that the strenuous work would make his son ill, and that he would do nothing else than drawing and painting during his convalescence. Two years later, after his recovery, Henry enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. By that time, most artists refused to accept black apprentices. He was the first and only one. Despite the racial abuse, he was inspired by his teacher Thomas Eakins and persisted in his dream. His début was the very next year, in 1880, at the Pennsylvania Academy Annual exhibition.

He soon began to sell his work, however his increasing confidence as an artist didn’t make up for the racism he had to deal with. In 1891 he travelled to Paris where he joined the Académie Julian and the American Art Students Club of Paris. In this brand new world, the racial issue mattered little among artistic circles. It was easy to feel at home – and so it became for the most of his life.

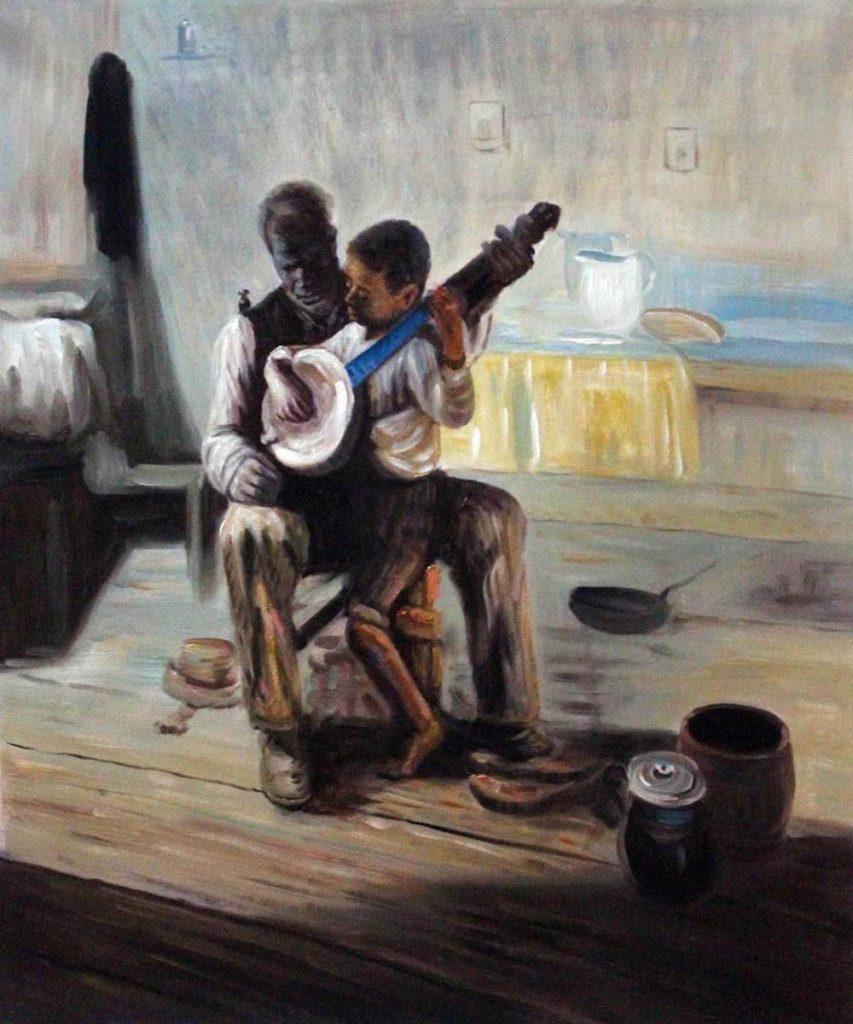

Works such as “Daniel in the Lions” and “The Resurrection of Lazarus” raised immensely Tanner’s reputation among the artistic elite, and defined his path which mostly specialized on Biblical Themes. Throughout his life he travelled to Algeria, Egypt, Palestine and Morocco to find further references and inspiration to perfect his work. However, it was on a brief return to the USA that he produced his most famous work: “The Banjo Lesson”. Not only it was his first masterpiece, with unmatched technical skills, but also a form of protest and liberation. In this work – as well as in “The Thankful Poor” – Tanner proudly assumed his racial identity with mastery suited for greatness. He disrupted the habit of grotesque caricatures and rural poverty, to finally represent black subjects with knowledge and dignity. It was a turning point in African-American Art History.

In 1895 Tanner returned to Paris to consolidate his reputation as a salon artist and religious painter. Tanner met Jessie Macauley Olssen in 1898, a Swedish-American opera singer and a model for his paintings, who became his wife the very next year. In 1923, after serving with the Red Cross, Tanner was made a Knight of the Legion of Honour for his artistic work, painting images from the front line.

Two years later, in 1925, his happy marriage came to an end with Jessie‘s death, leading him to a profound grief. After selling their family home in Les Charmes, Tanner took care of his son and never remarried. He channeled his energy to develop his work and technique with such dedication, that he is still today considered the greatest African American painter. With this legacy behind, Henry Ossawa Tanner died in his sleep on May 1937 in Paris, and he was buried next to his wife in Sceaux, Hauts-de-Seine.