Art

Did Impressionism Rip Off Macchiaoli?

Did you know there was an Italian Proto-Impressionism? The Macchiaoli movement was active in Florence during the mid-nineteenth century. A few disenchanted, youthful men were fed up with the “Neoclassical” movement and met at Caffe Michelangiolo with other creatives to discuss politics and the rebirth of a type of art to encompass the chiaroscuro of Caravaggio and the whimsical realism of Rembrandt. Macchia translates to “stain,” inspiring the name for the Macchiaoli art movement.

Macchiaoli (1855-1862) preceded Impressionism by a difference of about ten years, and the movements have quite a few things in common historically. When paired side by side the similarities are significant enough for any art enthusiast to raise a questioning eyebrow. A few of these strange similarities include:

- The formation of each movement was in opposition to a “Neoclassical” and politically correct school with a very strict definition of art. The Impressionists made their own outdoor gallery to show their works in the early 1870s by the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The Macchiaoli painters were noted to be very anti-academy.

- The name of each movement was coined by a critic in a review with similar meanings and intended disdain. For Impressionism: The paintings were incomplete child’s play, and the name of the movement was taken from Monet’s “Impression, Sunrise” painted in 1872. For Macchiaoli: The paintings were made up of “stains” and were no more than sketches in a harsh review published on November 3, 1862, in the journal Gazzetta del Popolo, first mentioning “macchia“.

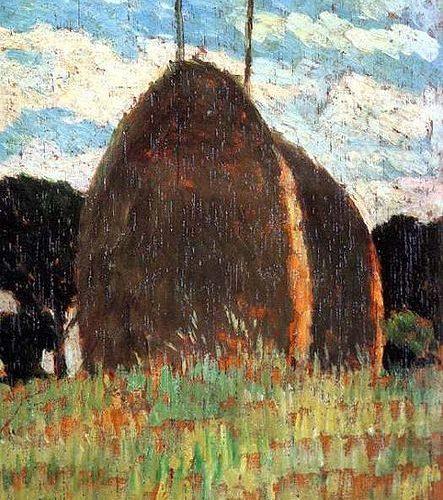

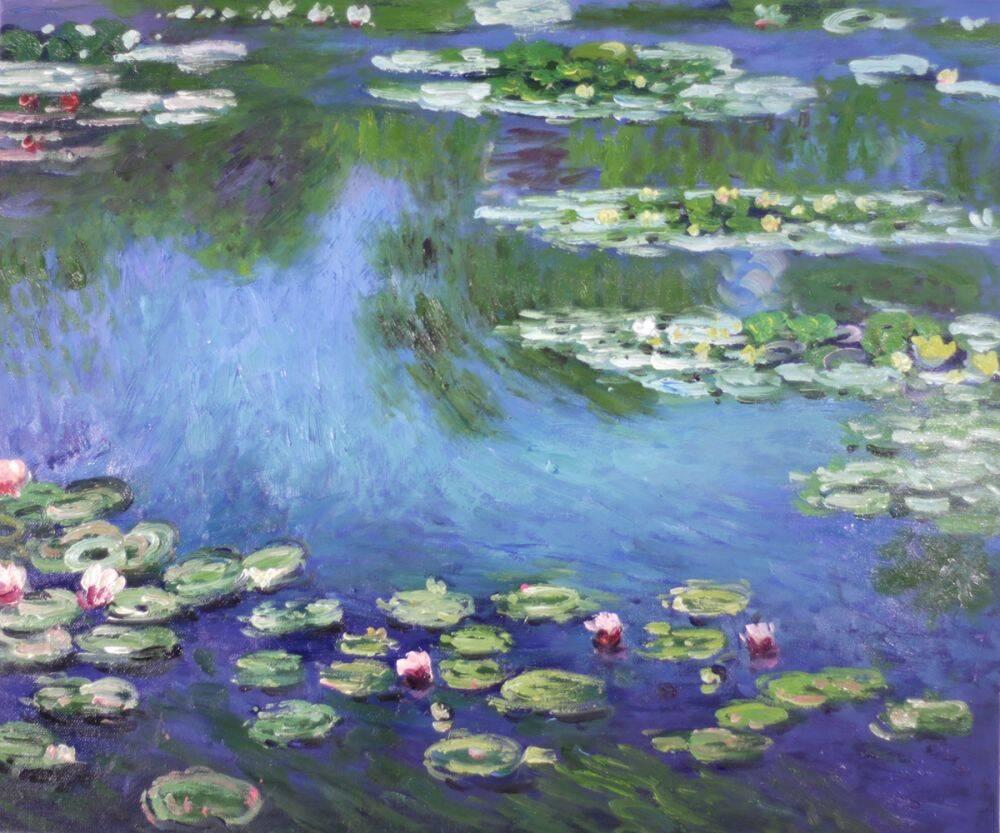

- Haystacks. (This one is a stretch.) Giovanni Fattori today is recognized as a prominent Macchiaoli artist. For a time he focused on haystacks as a subject matter, much like Monet’s prominent Haystacks series. Many Macchiaoli artists relied on Plein-air sketches, but many Impressionists skipped the studies and rendered the light immediately on canvas as a painting. Regardless, both movements shared a tendency and insistence on a Plein-air element.

- Each movement surrounded civil war and unrest. Macchiaoli: The second Italian Independence war in the late 1850s. Impressionism: The Franco-Prussian War in the early 1870s.

Interestingly, Macchiaoli had an influence through Italian landscape painter Giovanni Costa who was associated with the French painter Corot. “The typical Macchiaolo elongated format, however, owes more to Corot {curiously overlooked}…Giovanni Costa who knew the Frenchman’s work had already adopted this format in the early 1850s,” relays art reviewer Sandra Beresford (255.) Costa has no mention as actively a part of the Macchiaoli movement by scholars or critics, but his work and those he was influenced by had its impact on the movement. Beresford also mentions that Costa wrote to the art critic Diego Martelli at times.

Interestingly, Macchiaoli had an influence through Italian landscape painter Giovanni Costa who was associated with the French painter Corot. “The typical Macchiaolo elongated format, however, owes more to Corot {curiously overlooked}…Giovanni Costa who knew the Frenchman’s work had already adopted this format in the early 1850s,” relays art reviewer Sandra Beresford (255.) Costa has no mention as actively a part of the Macchiaoli movement by scholars or critics, but his work and those he was influenced by had its impact on the movement. Beresford also mentions that Costa wrote to the art critic Diego Martelli at times.

Macchiaoli and Impressionism did have an art critic and enthusiast in common, one Diego Martelli. Art historian Norma F. Broude describes: “During the artist revolution which had taken place in Florence during the 1850s, Martelli, an early supporter of the Macchiaoli, told his audience “ . . . the macchia was found in opposition to form . . . it is said that form did not exist and since, in light, everything appears as a result of colors and chiaroscuro, the effects of nature should therefore be obtained solely by means of patches [macchie], either of the color or of the tone.” Like the conservative critics who had first attacked the Macchiaoli some fifteen years earlier, Martelli sees the macchia in opposition to “form”, but the meaning which he attaches to these terms are new” (406). Broude relays that in the 1860s and early seventies, Martelli’s writings reflect the concept of contemporary French art which was “then current among the Italians” (407). Broude reveals that Martilli “in Paris for the first time in 1863 he waxed enthusiastic over the paintings of Corot, Millet, and Courbet, while the work of Manet, which he saw for the first time at Salon des Refuses of that year, struck him…” (406-407). Scholars of Manet will recognize his later work as a precursor to the Impressionist movement.

Martelli became one of the first critics to support French Impressionism. Was Diego Martilli a spy for the French, who had a secret time-traveling device able to fling him back and forth between decades? Not likely. Scholars, such as Broude, indicate that in 1863, Paris was Martilli’s first exposure to Impressionism as we know it today and that Impressionism, as he witnessed it, was hardly inspired indirectly by him, though the connection is valid to the suggested element of influence.

Edgar Degas did paint Martilli in 1879. The painting now hangs in the National Galleries of Scotland. Common sense would have us suppose that Martilli shared some aspects of his knowledge of the Macchiaoli technique. Martelli was also friends with Macchiaoli painter Giovanni Boldini, who “learned enduring lessons from the Macchiaioli, reinforced by his exposure to Manet, Degas, and others in French Impressionist circles,” according to writer Roderick Morris in this New York Times article. With the Macchiaoli and Impressionist movements being merely a decade apart, artists from these movements would have inspired and grown from exposure to one another’s work. It’s not that Impressionism “ripped off” the Macchiaoli movement but shows evidence of cross-pollination in art rendering. Perhaps here we witness how the growth of art naturally progresses, just as various cultures across the world share very similar myths and traditions.

The Musée d’Orsay will host a show revealing several Macchiaoli paintings to the French public from Apr 9, 2013 – Jul 22, 2013.

Sources:

Beresford, Sandra. “The Art of the Macchia and the Risorgimento. Representing Culture and Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Italy (by Albert Boime).”Burlington Magazine. Apr 1995: 255. Print.

Broude, Norma F. “The Macchiaioli as “Proto-Impressionists”: Realism, Popular Science and the Re-shaping of Macchia Romanticism, 1862-1886.”Art Bulletin. 52.4 (1970): 404-414. Print.

Morris, Roderick Conway. “In Impressionist Paris, the Face of the Belle Époque.” New York Times. 13 Nov 2009: 1-2. Web. 18 Apr. 2013.